FT top MBAs for women ranking 2018

Publisher : MBA Office Mar.06,2018

Emily Jin is an MBA student at Shanghai Jiao Tong: Antai - the Chinese school offers the best MBA programme for women in 2018.

An MBA is a fast ticket to the big time. On average, those who complete a course with a top school can expect to earn six-figure salaries three years after graduation. But despite generous scholarships and campaigns to encourage them to apply, women are a minority on prestigious business school courses.

Four in 10 applicants on two-year, full-time MBAs in 2017 were women, compared with 33 per cent in 2013, according to the Graduate Management Admission Council. But women’s growing interest in business education has not led to more diverse MBA cohorts. Five years ago, women accounted for a third of students on the top 100 MBA programmes ranked by the Financial Times. Today, the figure has barely budged.

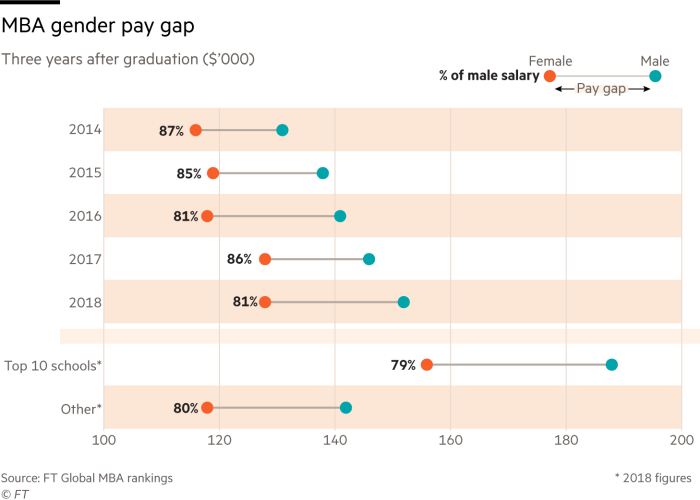

The average cost of an MBA is $100,000 plus an average opportunity cost, or the income lost from not working, of $103,000, FT data show. Given that women’s salaries on average were 91 per cent of their male peers before joining MBA programmes in this ranking, saving up the cost of such personal investment is a greater sacrifice for women.

And there is evidence to suggest that an MBA exaggerates the gender pay gap: three years after graduation women on average made 86 per cent of their male peers’ pay, the data reveal.

Women receive a lower return on investment, says Elissa Ellis Sangster, executive director of Forté Foundation, a consortium of business schools and companies trying to improve women’s access to business education. But, she adds, “the return will still be high”.

Either way, women need to know that their investment is going to pay off. That means taking into account which MBA will help them counter future pay discrimination, and which schools are best at teaching and developing their female graduates while promoting them to employers.

The FT’s Global MBA ranking, published in January, does not capture whether women do as well as their male peers on graduation. That is why, for the first time, the FT has ranked business schools according to their outcomes for women — and the results are significantly different.

The top MBAs for women ranking tells us at which schools women perform best, and where there seems to be a gap between the outcomes of male and female graduates.

Some schools that rank in the mid-range of the Global MBA ranking shoot to the top in this new ranking. Most of those are based in China, including Shanghai Jiao Tong: Antai, which tops the list.

Emily Jin graduates from Antai’s part-time MBA programme in May. She says Chinese women’s interest in business education is growing as they get richer. “Especially in Shanghai, women are more and more independent and decide to spend their own money to develop themselves,” says Ms Jin. Originally from Fuzhou in southern China, Ms Jin has worked in Shanghai for many years. She chose to study for an MBA in order to develop her network and switch from a career in marketing to a more innovative area, perhaps artificial intelligence, she says.

Why study part-time? “I have a son, and so I needed the flexibility to keep working,” she says.

Four Chinese schools make the top 50. So what do Chinese business schools do differently that works for women? The answer lies in the workplace, says Mantian Wang, director of Antai’s International MBA programme. Although Chinese society encourages women to start a family at an early age, women are also offered equal opportunities at work — and they grab them. “We provide flexibility to our students on a case-by-case basis,” Ms Wang adds, pointing out that women are more likely to ask for flexible schedules to spend time with their families. “But we also have a tradition of grandparents helping out a lot with the family.”

The new ranking also sheds light on which business education providers really work for women. In the methodology, alumna salaries three years after graduation — both the absolute figure and increase — were given a weight of 15 per cent each.

We considered other criteria, such as gender balance among students and faculty, and the extent to which female graduates say they achieved their goals. But success for women is not just about take-home pay. It is also about the difference in pay after graduation. So we measured the average female graduate salary as a proportion of the average male salary after three years in the workplace, and gave that criteria equal weight.Are you a female MBA graduate? We are keen to hear your personal stories on gender pay gaps.

Released: 20180305

Media: Financial Times

https://www.ft.com/top-mbas-for-women?from=groupmessage